Ed Pennington and Bruce McDonald obtained a successful result in an action against anonymous counterfeiters engaged in a phishing attack against SGR client Bote LLC, a manufacturer of surfboards, kayaks and stand-up paddleboards (SUPs). Bote LLC v. BOTEBOARD.COM and John Does 1-10 et al., No. 1:21-cv-00612-LMB-MSN (E.D.Va.). By serving subpoenas and demands on multiple registrars, proxies, website hosting services and privacy providers, the client was able to take down 81 “copycat” websites spanning an array of top level domains that were unamenable to jurisdiction in a single court.

The case had elements of so-called “cybersquatting” but was more complex than a typical cybersquatting action, which is only available where a URL incorporates or is otherwise confusingly similar to a client’s trademark, whereas the URLs in this case included many that had no resemblance to the client’s trademark and were administered by registries and registrars outside the United States, so that jurisdiction over all of them could not be obtained in a single court action.

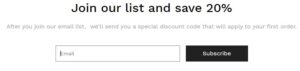

Each of the copycat websites imitated the client’s website at www.boteboard.com and displayed the client’s goods, using images copied from the client’s website, soliciting personal information from consumers (“phishing”) by means of a “subscription portal” appearing as follows in a manner that allowed the anonymous defendants to impersonate the client by communicating with the client’s customers:

The copycat websites displayed images of the client’s products such as the following photographs of BOTE® products copied from images appearing on the client’s website:

The client, upon the exercise of due diligence, was unable to discover the email addresses or other contact information for the registrants of the associated URLs, as such information was concealed by the registrars and hosting service providers. The client issued correspondence to the providers demanding disclosure of the registrants’ name and contact data, but had no response except for a series of automated messages denying responsibility for anything and providing non-functional links where a phishing report could ostensibly be filed, but which led to the following web page:

The client obtained an ex parte temporary restraining order shutting down the copycat website at www.bote-board.com under the in rem provisions of the Anticybersquatting Consumer Protection Act (“ACPA”), Pub. L. No. 106-113, 113 Stat. 1501 (1999), codified at Section 43(d) of the Federal Trademark Act of 1946, as amended (the “Lanham Act”), 15 U.S.C. § 1125(d). The complaint alleged trademark counterfeiting under Section 32(1) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1114(1), and false designation of origin in violation of Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a).

Jurisdiction was obtained in the Virginia federal court as the counterfeit domain name was registered in the “.com” top level domain, which is administered by Verisign, a domain name registry located in Virginia. The TRO was granted because the URL was confusingly similar to the client’s registered trademark. To that extent, the case would have been an ordinary in rem cybersquatting action. However, the circumstances rapidly escalated.

No sooner had the TRO issued than two newly appearing copycat websites were discovered at www.botesports.com and www.botespecial.com. The client accordingly obtained an amendment to the original TRO shutting down these websites in the form of an order directing transfer of the corresponding URLs to the Virginia-based domain name registry. Even then, the case was still an ordinary in rem cybersquatting action.

At this point, however, the client began to discover scores of newly appearing copycat websites with associated domain names, 81 in all, that were neither confusingly similar to the client’s trademark nor registered in top level domains administered by a Virginia-based registry, e.g., www.blossompures.shop, www.citygrounds.club, www.diamillion.shop, www.diyprinter.top, www.giantteddy.shop, www.gradys.shop, www.lampuga.vip, www.lobsterfeat.vip, www.ronixwakes.club, www.swingdesign.top, www.turntable.club, www.turntable.vip.

The client now faced an obstacle inasmuch as in rem jurisdiction over the newly discovered copycat websites could not be obtained in Virginia, or in any single court, because the registries associated with the corresponding top-level domains were located in such places as the United Arab Emirates (.ONLINE), and the registrars were located in the Czech Republic, China, and Denmark.

Responding to the circumstances, the client issued a large number of subpoenas and demands on each of the domain name registrars, proxies, hosting services, privacy services, and their alter egos, associated with the corresponding URLs, collectively. Each time that a newly appearing copycat website was discovered, a new subpoena and demand was served on each of the relevant domain name registration service providers, directed to the particular URL, resulting in scores of subpoenas served on a multiple service providers.

The providers who were servicing multiple copycat websites and corresponding URL’s received multiple subpoenas, each directed to a particular URL, with correspondence pointing out that the anonymous domain name registrants, and by association the providers, were not only violating the Lanham Act but damaging the public by fraudulently concealing the origin and source of goods and services in U.S. commerce in violation of the federal mail fraud, fictitious name and wire fraud statutes, 18 U.S.C. § 1341, 1342 and 1343.

The client calculated that if its subpoenas and demands was accompanied by correspondence to the service providers that was respectful in tone and content, and that prevailed upon their corporate citizenship to partner with the client against surreptitious action by fictitious and anonymous domain name registrants engaged in a manifestly criminal conspiracy, the client could enlist the cooperation of the registration service provider community as a whole to shut down the criminal enterprise. That result in fact occurred, and moreover, the client was able to identify the source of the anonymous activity in China.

The identification of parties in interest behind fictitious and anonymous ownership of domain names is a complicated business, because investigation typically leads to gmail.com and other spurious email addresses which themselves are fraudulently registered. Further, requests for payment information that would reveal bank accounts associated with such URLs are universally rejected, and a party under such circumstances is not in a position to enforce the subpoenas, though a particular registration or email service provider will not necessarily know that.

In this case, however, the client was able to identify the actual source of the counterfeit activity because one of the multiple email addresses discovered through such efforts traced back to a brick-and-mortar company in China. The information was discovered by a subpoena to Google demanding information about a gmail.com address that had been used to register one of the counterfeit URLs. The client correctly calculated that if it served enough subpoenas and demands on all of the service providers associated with each of the copycat websites, respectively, enough information would leak out to identify the actual perpetrators.

In the end, the client was prepared to serve process in China and pursue a default judgment against the unmasked John Doe defendants in the Eastern District of Virginia, or a corresponding damage action in China. However, it was unnecessary for the client to do either of those things, or to incur any of the associated costs, because the Internet domain name registration service provider community, as a whole, elected to partner with the client in response to the client’s subpoenas and respectfully worded demands, instead of resisting them.